Silent no more?

Introducing 'Silence of the Gods'

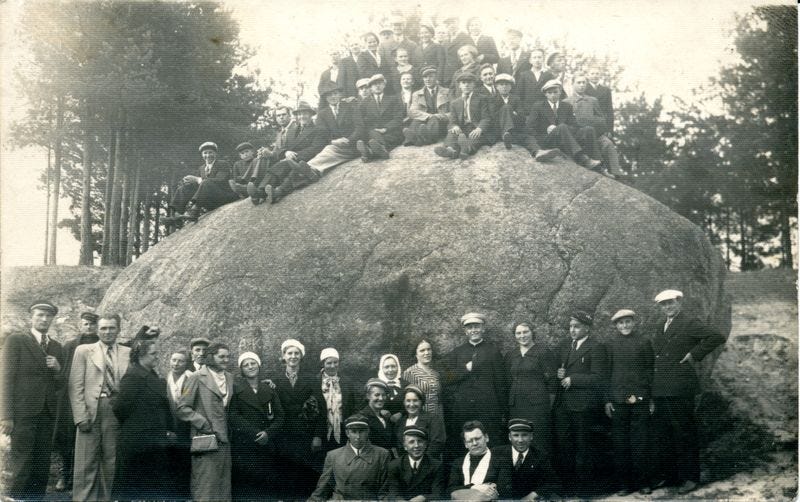

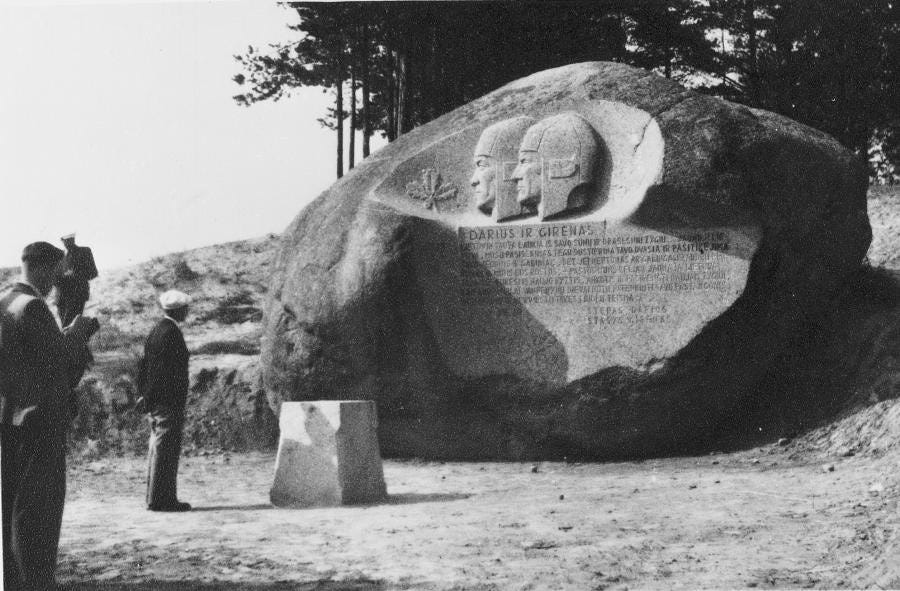

Silence of the Gods, my new book about the last pagan peoples of Europe, is published today by Cambridge University Press. The book opens in August 2000 at the foot of an enormous Lithuanian glacial erratic boulder in the forest of Anykščiai, where I am eating a picnic of tomatoes and dark rye bread purchased earlier that morning from a market in Panevėžys. The rock, known as Puntukas, is the second largest boulder in Lithuania, and today it’s an important local tourist attraction – not least because in the dark days of Nazi occupation someone carved the faces of two 20th-century Lithuanian heroes (the tragic pilots Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas) into the rock in deep relief. Millennia ago, this vast rock made the slow journey along a glacier from Finland before finally being left behind in what is now Lithuania as the glacier melted at the end of the last Ice Age.

Silence of the Gods begins at Puntukas, because it was at Puntukas that my journey to understand Europe’s last pre-Christian religions originally began. For this was a site unlike anything I had ever encountered in Britain, its long life and significance defined by three distinct moments: the melting of the glacier, its period as a ‘sacred’ rock, and its reinvention as a Lithuanian national monument. Puntukas marked for me the beginning of an effort to make sense of the relationship between humans and their environment, and between humans and the gods their environment somehow embodied – an effort to recover a lost European religiosity and a kind of spiritual awareness that, while historically remote to western Europeans, is not wholly forgotten here in the birch forests of Lithuania. So let’s turn back the clock, and try to catch a glimpse Puntukas at three moments in its long life.

The melting of the glacier

The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia are littered with glacial erratics (as is Finland) – geological aliens in countries that have no major hills or mountain ranges. Such objects are not unknown in Britain, but they are seldom on such a scale. The glaciers in this part of Europe melted around 11,700 years ago, leaving behind the detritus from millennia in which the ice had been reshaping the landscape. As the ice melted, trees arrived – and, with them, the ancient predecessor of today’s forest of Anykščiai grew up around the marooned boulder. In due course it was not just trees and animals who arrived, but also human beings – hunters for whom any unusual natural feature, like an erratic boulder, would surely have been a landmark and a place of memory – a reminder that this was a good place to hunt, or a prompt to remember a successful expedition, or even a warning to turn back from a place of danger. From the very beginning, a natural object as large as Puntukas demanded recognition, and a relationship with human beings.

The sacred rock

We don’t really know who these hunters were – these first Baltic people who inhabited the shores of a vast inland lake rather than the Baltic Sea of today, connected as it is to the North Sea. It’s possible that they were Uralic people – distant ancestors of today’s Livs and Estonians. Perhaps they were related to the Sámi who later moved to the furthest northern reaches of Fennoscandia. But they were certainly not the people we call Balts, those speakers of an Indo-European language (ancestors of the Lithuanians and their Latvian brethren) who burst out from the Ukrainian steppes along with their Slav cousins in antiquity. Whoever they were, the earliest settlers received the Neolithic agricultural revolution about 5000 years ago, and they made the transition from hunting and gathering to slash-and-burn agriculture. Over time the land became cultivated; great forests remained, but the population remained in one place. New peoples came, bringing horses and speaking a branch of a new family of languages that was conquering Europe. These were the Lithuanians, and they had a new word for the rock – akmuo – and a new word to describe it: šventasis, holy.

For stability and agriculture had produced a new way of looking at the landscape. Whatever was unusual, whatever marked boundaries, became sacred: low hills and rivers, lakes, pools and bogs, large and ancient trees, and the forest itself – and, of course, the large glacial boulders that only the gods could have placed in the landscape. And people began to interact more intimately with this sacred landscape - they gouged holes in the big boulders; cavities for offerings, perhaps, or memory places to memorialise rituals performed, to track the passage of time, or even to record the local topography or the night sky. We cannot know for sure. The glacial erratics became places of gathering and sacrifice, set as they were in clearings of the forest that were themselves sacred as groves – natural absences of trees that provoked awe and invited veneration. Fires were lit, libations poured and prophecies divined through long centuries; and even when men clad in metal rode into the land plundering, killing and burning in the name of their strange jealous god, there were always places deep in the forest – places like Puntukas – that the Crusaders would never reach.

Later, when peace reigned again, black-robed priests came to the countryside every summer in an effort to persuade the people to leave aside their old ways – to make confession and promise they would never sacrifice again to Perkūnas and Žemyna, father thunder and mother earth. But it was difficult to stop old traditions – after all, the god of the priests who babbled in Polish and Latin was powerful, but there was no sense in angering the lords and ladies of the forest for no good reason.

And then came war, and slaughter, and cold, and famine, and dying. The old people who remembered days of celebration at the rock were dwindling. A new church was being built, within walking distance. It was easier to worship the priests’ god there than it was to try to remember the old ways of the forest. And finally the Russians came, and the people ran to the priests and clung to the churches because at least their Polish and Latin babble was familiar, compared to the strange ways of the Russian priests and the cruelty of soldiers who resented a foreign land.

The monument

It’s the summer of 1943. Bronius Pundzius, a sculptor and tutor at the Kaunas School of Applied Arts, has avoided the patrols of grey-clad soldiers between Kaunas and Anykščiai, cold-eyed men without conscience who worship their Führer and treat the Lithuanians as a lower race. Like the partisans, he is deep in the forest now, working in secret with a handful of his students to break away the face of the huge rock and to carve his and his nation’s resistance into it forever – the faces and words of two men who became for a brief time the heavenly twins, the Dievo sūneliai who ride through the heavens – not on supernatural steeds but in a little orange aeroplane that bore the name of its resurgent nation. Lituanica had been the slender thread that connected a free Lithuania to the New World, where so many Lithuanians had emigrated in search of freedom, and it seemed to promise a different destiny for the nation, where Lithuania was accepted as an ally of the United States and the great democracies of the west.

And then, just as Lithuania was now overwhelmed by the Nazi occupiers, so German soil had swallowed the pilots on the cusp of their moment of triumph. They never quite made it to Lithuania; but in death they now stared in profile towards a seemingly impossible hoped-for destiny for Lithuania from the face of the ancient rock.

***

The single constant across these three moments in the life of Puntukas is the fact of the rock itself. Peoples, languages, cultures and armies come and go; the deep landscape remains. And it is from the deep landscape, so I argue in Silence of the Gods, that responses to the sacred emerge. There are cupmarked rocks in Finland and the Baltic states – most of them glacial erratics – where there is archaeological evidence of continuous ritual use from the Neolithic period to the 20th century. Historians of religion love this sort of continuity. But this is continuity so extreme that it speaks as much to the discontinuity of its surroundings: for the people who began the ritual use of such stones were completely different in language and culture from those who continued it into recent times. And as to purpose and intent, the last people who made ritual offerings at sacred stones in the Baltic in the interwar years were as much in the dark as we are about the motivations and thinking of the prehistoric people who first dug into the stone. Religions and traditions change; continuity is to be found in the landscape and the environment. Even the work of Bronius Pundzius in carving the rock into a national monument to two dead pilots was, in its own way, a religious act – there is a fine line between ritualised nationalism (so common in the Baltic republics) and religion – indeed, perhaps no line at all at times. Freedom is a religion when any escape from tyranny seems like a miracle.

Silence of the Gods is a book about the nature of human religiosity as much as it is about the specific peoples whose religious histories it tries to trace – the Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Sámi, Maris, Udmurts, Chuvashes and so on. As well as arguing that religion is influenced by the environment and the landscape, I also argue for the creativity of peoples left in a religious ‘no man’s land’, caught between the destructive intervention of missionary Christianity and cultural forgetting of their own traditions. What resulted was ‘found’ religion – a process of religious bricolage where a community’s approach to the sacred was cobbled together from half-understand elements of Christianity, half-remembered pre-Christian traditions and seemingly instinctive responses to the landscape. The search for the high place, the search for the shaded grove, the search for the ancient arboreal witness, the search for the life-giving water – all these things rendered a landscape sacred, to any people in any age. That is why Silence of the Gods is a book about the future as well as the past; human religions tell us about humans – who we were and who we are, and perhaps who we will be. The beauty of Eastern and Northern Europe is that the kind of ‘found religion’ we are accustomed to associating with prehistory in western Europe is much closer to the surface of the historical record. But this isn’t just a book about strange people with strange names and odd languages – that was never my intention. Whoever you are, whatever your ancestry, in one way or another it is a book about you.

I've just ordered my copy of 'Silence of the Gods' from my local Bricks & Mortar store - I'm very much looking forward to reading it when it arrives - Thank you.

Just ordered my copy! Looking forward to reading!