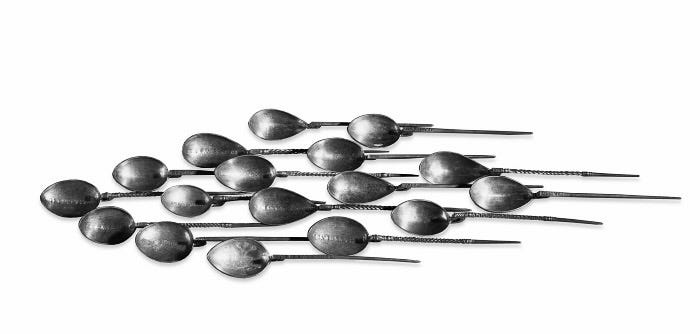

The Thetford Treasure is, in my view, the single most interesting archaeological discovery from the last phase of Roman Britain. It is the principal subject of a chapter in my book Twilight of the Godlings, and partly inspired me to write that book in the first place – since I had found myself writing about the Thetford Treasure in an earlier book, but it felt like too much of a digression. It is an assemblage that hints at bizarre religious experimentation and syncretism, with spoons that famously bear native British epithets for the archaic Roman god Faunus, combined in some cases with Christian inscriptions. There are also finger rings bearing gnostic and esoteric imagery. You can read about my theories on the Thetford Treasure in Twilight of the Godlings – but I was excited to read a recent article by Ellen Swift that proposes some important revisions to the initial (and still authoritative) 1983 discussion of the treasure by Catherine Johns and Timothy Potter.

Ellen Swift’s article can be read in full here, and a lot of it is rather technical. It is not, like much that has been written on the treasure (including by me) a reinterpretation of the treasure’s potential religious or cultic significance, but rather a close stylistic examination of specific features of the jewellery in the assemblage to propose a much later date for the treasure than Johns and Potter imagined. Following the archaeological orthodoxy of the 1980s, Johns and Potter began with the assumption that the ‘end’ of Roman Britain in 410 represented a terminus post quem for all Roman archaeology in the UK. Since then, the notion that Roman Britain came to an abrupt end in 410 has been somewhat finessed; consider, for example, the surprising discovery of a sophisticated mid-5th-century mosaic at Chedworth in 2020. Indeed, we should perhaps not be surprised that Roman Britain had a long post-Roman afterlife – the visit of St Germanus of Auxerre described in the Vita Germani (in 429) seems to depict a peaceful and well-ordered Roman-style society in Britain (apart from the Pelagian heresy) two decades after the departure of the legions. Investigations at Vindolanda are also discovering more and more evidence of post-Roman use and habitation, and it is clear that Britain did not degenerate immediately into an embattled society of people living in huts on top of repurposed Iron Age hillforts waiting for Arthur to defend them from the Germanic barbarians.

In brief, Swift analyses the dolphin- and bird-shouldered rings, multi-gem jewellery and face-mask rings found in the Thetford assemblage, noting from comparisons with examples from elsewhere in the Roman world that these designs are not known much before the mid-5th century. Furthermore, she notes that the Hoxne Hoard was discovered after the Thetford material, and seems to date from the 5th century – in all likelihood after 410 – so there already exists an analogous East Anglian assemblage that might date from a similar period (although the dating of the Hoxne Hoard – in whose discovery my father-in-law, incidentally, played a key role – is fraught). Swift also notes the appearance of a cross rather than a Chi Rho on one of the Christian-inscribed spoons from Thetford, and crosses do not appear until the 5th century. Likewise, some of the spoons have handle inscriptions rather than inscriptions on the bowl – a late development not seen elsewhere in the Roman world before around 420.

In short, Swift makes a solid archaeological case for the deposition of the Thetford assemblage between 420 and 440, definitively after the formal end of Roman Britain. It should be noted that this does not directly affect the interpretation of what are (in my view) the most interesting items in the assemblage, the Faunus spoons (which still date from the late 4th century). But it is necessary for Swift to rely on this sort of analysis of stylistic forms for dating because, notoriously, the Thetford Treasure lacks archaeological context and was the product of illegal metal-detecting on a site that was then built over before archaeologists could analyse it. Swift is critical of John and Potter for assuming the essential unity of the Thetford Treasure as a group of objects produced and deposited within a ten-year period in the late 4th century. It now seems that the objects had a much longer history before they were buried at Gallows Hill.

But if this is true – and this is the really exciting implication of Swift’s research – the Thetford Treasure does not belong to the ‘official’ end of paganism in Roman Britain (associated with the suppression of pagan cult and closure of temples between 381 and 394), when most of the religious objects recovered from late Roman Britain seem to have been buried. Does this mean pagan worship continued at Gallows Hill beyond 394? As things stand (and believe me, I have explored the archaeological literature on this question very thoroughly indeed) there is no clear evidence for any survival of Romano-British pagan cult in Britain beyond the end of the 4th century. No 5th-century paganism, or at least no evidence for it. Although the specific site of the Thetford Treasure could not be investigated, at Fison Way very close by the fill of a ditch around some sort of structure (perhaps a timber aisled building or gate that was part of a religious complex) was carbon-dated to 480 ± 60 AD, so this could be the first evidence of 5th-century Romano-British paganism. (5th-century Romano-British paganism is one of those things people tend to assume must have existed, but without evidence). Quantities of metal finds and coins from the associated structure are consistent with a shrine – and the discovery of a single curse tablet clinches the identification. As Swift declares, ‘Since wider evidence found at the site confirms the religious context established by the spoon inscriptions, this means, remarkably, we must envisage a pagan cult center surviving into the 5th c.’

But is the Thetford Treasure as straightforward as the cult-treasure of a shrine buried in or near that shrine when the shrine was discontinued? It is probably more complicated than that, and Swift discusses in detail the questions associated with the hoard’s religious significance. Could the treasure have been someone’s personal property hidden at the shrine for safekeeping, rather than the treasure of the shrine? Objects being owned by a shrine did not preclude their future economic exploitation, and Swift notes the significance of spoons in a post-Roman Britain without coins, since they usually weighed exactly one ounce and therefore acted as potential bullion. Could the treasure be evidence of post-Roman bullion-exchange? The damage to the jewellery points to its primarily economic significance – it is not damage consistent with the ritual ‘killing’ of objects offered to shrines that is well-known in Roman archaeology, and seems to suggest the work of a jeweller.

So the context of the hoard’s deposition is anyone’s guess, really. Was it buried by a shrine official as a financial deposit for the shrine’s benefit, to be recovered at a later date? By a thief who had plundered a nearby shrine and needed somewhere to hide the loot? By a shrine official at the ritual closing of the shrine in a Christianising world? Or by a jeweller who made use of a convenient collapsing shrine building to provide a memorable location for a deposit of raw materials to use at a later date? But perhaps the precise circumstances of the treasure’s deposition aren’t so important; what matters is how these materials came to be together, as well as their general association with the rich ritual and religious landscape of Gallows Hill, which stretches back to the Iron Age. Swift concludes that ‘all this evidence confirms the religious use of the site independently of the spoons with Faunus-related inscriptions, and shows that all the objects were deposited at a temple on this site.’ We have, in other words, convincing evidence of what may be the oldest Romano-British pagan cult yet confirmed by archaeology in Britain – paganism, perhaps, in the age of Patrick, a tradition cut short by the arrival of a new people in the east of Britain, with their own gods…

Extremely interesting and hopefully future finds will cast more light on the immediate post Roman period. In that regard, I very much liked the final sentence of your second paragraph.)

Fascinating.